20 valuable lessons for games designers

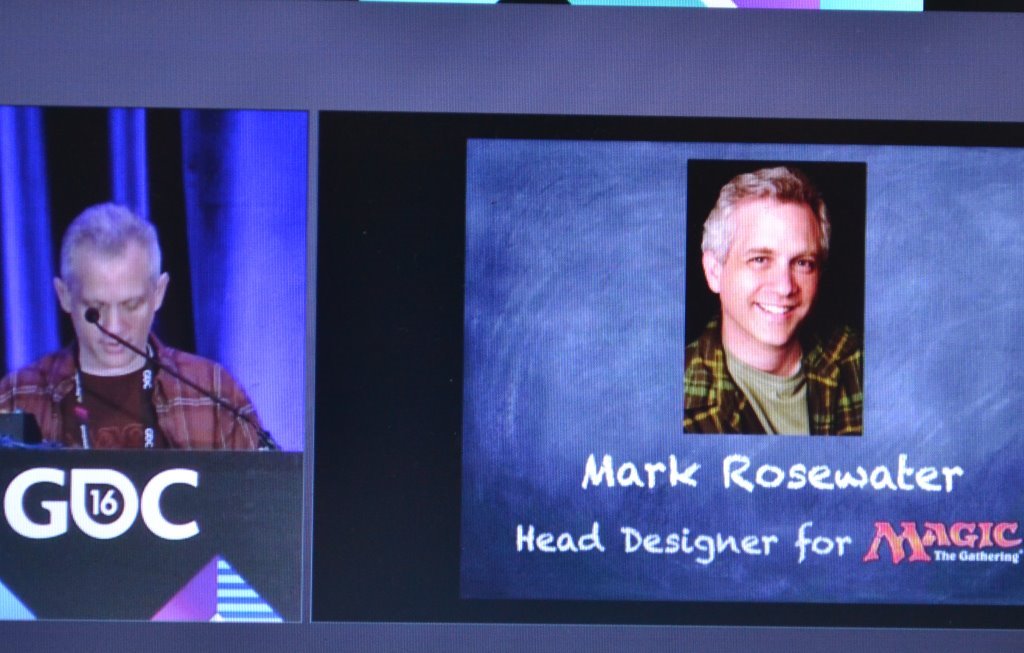

Game Developers Conference, San Francisco – Mark Rosewater, Head Designer for the “Magic: The Gathering” shared his experiences that he gained over the past 20 years on designing, improving, and advancing the same game. Since 1995, he has been working for Wizards of the Coast which created Magic: The Gathering. He mentioned not many games survived that long time and it is no wonder that the game went though many changes. In the period of 20 years they made: 86 randomized booster products, 69 non-randomized products, online licensed and other miscellaneous products, and produced over 14,000 unique cards.

There were also many lessons learned that the game designers can adopt in the process of building their games. Rosewater named 20 lessons. One for each year of his work.

Lesson 1: Fighting against human nature is a losing battle.

Knowing your audience is a key. Since your audience are humans, you know that they can be a little stubborn and have their own habits, so don’t try to change the players to match the game. Change your game to match the players.

Lesson 2: Aesthetics matter. Don’t fight human perception.

Aesthetics is also known as the Philosophy of Art or Science of Beauty. The idea of aesthetics is to study how humans perceive the world. There are differences between individuals, as well as common things that are aesthetically pleasing. In games, players expect the components of their game to have a certain “feel”. That is not only means visual aesthetics, but also things like balance, symmetry, and pattern completion. If any of these components are missing, it makes players feel ill at ease, distracts them from focusing on the game, and makes them pay attention to what your game isn’t instead of what it is.

Lesson 3: Resonance is important.

The audience already has preexisting emotional responses that the game designer can build upon. For example Magic did not invent zombies. Players come to the game with a pre-built emotional relationship with zombies that were created from years of watching pop culture. As a game designer, that’s a tool you should make use of.

Lesson 4: Make use of piggybacking.

Piggybacking is a use of preexisting knowledge to front-load game information to make learning easier. You don’t have to teach players things they already know, like killing a black cat is a bad luck.

Lesson 5: Don’t confuse “interesting” with “fun”.

There is 2 types of stimulation. There is intellectual stimulation (“interesting”) and emotional stimulation (“fun”). Looking at the cards is intellectual stimulation. Playing with the cards is emotional stimulation. We think about ourselves as intellectual creatures but we tend to make most of our decisions based less on facts and more on emotions. So, your game can speak to your audience on intellectual level or you can speak to them on emotional level. Both are valuable, but when you speak to the player on an emotional level, you are more likely to create player satisfaction.

Lesson 6: Understand what emotion your game is trying to evoke.

To be successful with a game you need to know what you want your audience to experience. What emotional response are you trying to create? You must continually ask yourself “What impact will this game choice have on the player experience”? And if it doesn’t contribute to the overall experience then it has to go.

Lesson 7: Allow the player the ability to make the game personal.

It is important for your players to have personal connection with your game. The more the players feel the game is about them, the better they will think of it. How do you do it? Provide a lot of choices, give them different resources, different paths, different expressions. Give the player the ability to choose (and not choose) things, allowing them to feel that what they choose is “theirs”. In Magic: The Gathering, the players can choose: colors, creatures, characters, factions, illustrations and the frames. There are many options available.

Lesson 8: The details are where your player falls in love with your game.

The players want to find a piece of game to call their own. The details matter because the individual will bond with the game through them. What might seem insignificant is anything but that. A small detail might only matter to a tiny percentage but to that percentage it could mean everything.

Lesson 9: Allow your players to have a sense of ownership.

You need to give the players an ability to build things that are uniquely theirs. The players don’t just create a deck of cards, they create THEIR deck: something what personally represents them. So when their deck wins, they win, because the deck is no longer just part of the game. It is an extension of themselves.

Lesson 10: Leave room for your player to explore.

Don’t always show the players the things you want to see. Let your players to find them. Let them discover things. Because if they find them, they will be more invested.

Lesson 11: If everyone likes your game but no one loves it, it will fail.

Players don’t need to love everything in your game, but they need to love something. Something they feel strongly about. Don’t worry that the players will hate something. Worry that no one will love anything, because things that evoke strong responses will most often evoke strong responses in many directions. This means that is almost impossible to make some players love something without making others players hate it. In fact some players enjoy hating what other players love. So stop worrying about evoking a negative response and instead develop something that evokes a strong response.

Lesson 12: Don’t design to prove you can do something.

Creative people tend to have larger egos, because it takes ego to will something into existence. Having an ego is fine but you can’t let your ego drive your motivations. You goal is to deliver an optimal experience for your target audience. Your decisions have to serve your game and not you. So, ask yourself: Is this decision helping me achieve the optimal experience for my target audience or is it being done to fulfill an inwardly facing need for self-satisfaction? If the answer is the latter, you are doing it for the wrong reason.

Lesson 13: Make the fun part also the correct strategy to win.

It is not the players’ job to find the fun, it is your job as a designer to put the fun where they can’t help but find it. Because when the players sit down to play the game there is an implied promise from the game designer that they will have fun. Remember – you have to make sure that what it takes to succeed at your game is the very thing that makes it fun. Fun can’t be tangential. It has to be the core component of your game experience.

Lesson 14: Don’t be afraid to be blunt.

Artists tend to prefer subtlety. They think show, don’t tell. But sometimes subtlety doesn’t work. People can just miss the obvious. For example in Magic we use the keywords to make sure players can focus on the mechanics.

Lesson 15: Design the components for the audience it’s intended for.

When you aim to please everyone, you often please no one. All your players don’t want the same thing out of your game. It is important to understand what different kinds of things your players want and to understand different kind of players you have.

Lesson 16: Be more afraid of boring your players than challenging them.

When you try something grandiose and it fails the players will forgive you, because they recognize you were trying to do something awesome. They respect the attempt and they even stick around to see what you will do next. But when you bore them, there is no such forgiveness, because making the same mistake is not the same as making a new one. When you bore the players, they resent you. Sometimes they stop playing.

Lesson 17: You don’t have to change much to change everything.

The game designers think there is never enough so they keep sticking more elements in. That creates complexity for your players and muddies the message of your game. You waste resources you could use later. Instead of asking how much I need to add? Ask – How little do I need to add?

Lesson 18: Restrictions breed creativity.

There is a myth about creativity that the more options available, the more creative people can be. But this contradicts what we know about how most brains work. The brain is amazing organ, it is very smart. When asked to solve a problem, most brains check their data banks and ask– Have I solved this problem before? If yes, it solves it the same way. Most of the time this is efficient. It lets you avoid relearning tasks each time you do them but it causes a problem with creative thought. If you use the same neural pathways you get to the same answers and with creativity that is not your goal. Here is the trick Mark shared with the audience. If you want to get your brain to get to new places, start from somewhere you have never started before. It forces you to think different in ways and create new problems to solve which results in new ideas and new solutions. What this means is that restrictions aren’t an obstacle but valuable tool.

Lesson 19: Your audience is good in recognizing problems but bad at solving them.

Your players have a better understanding of how they feel about your game than you do. You create the emotional response but they know what that is. They can easily tell when something is wrong. They are excellent in identifying problems. But they are not equipped to solve those problems. They don’t know your tools, your limitations. Use your audience as a resource, as a parameter to discover what’s wrong but take it with a grain of salt when they offer the solutions.

Lesson 20: All of the lessons connect.