by Lidia Paulinska | Dec 6, 2015

On December 2, 2015, in a live encore performance from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, Fathom Events presented Alban Berg’s masterful opera Lulu, featuring Marlis Petersen in the title role, Susan Graham as Countess Geschwitz and Johan Reuter as Dr. Schon. This was a very special performance, for it was to be Ms. Petersen’s final appearance in the role of Lulu after a professional career of delighting audiences here and abroad.

Alban Berg (1885-1935) was an Austrian composer, heavily influenced by Arnold Schoenberg and the culture of fin de siécle Vienna. He composed two seminal operas which were the most innovative and influential works of the 20th century: Woyzek (1925) and Lulu (1937). He is known for combining 19th century Romantic elements with Expressionistic idioms of the 20th century.

In this visually stunning production, the romantic lyricism of the music works in counterpoint to its atonality, and is complimented and contrasted with the stark, black and white expressionistic rear-screen projections, which, through their often violently changing patterns, create a kind of choral commentary on the action. Sudden giant swarths of black ink wash across the screen from one end of the huge Met stage to the other, and just as suddenly may dissolve into indiscriminate lines and circles with faces emerging from the seeming visual chaos. Characters on stage may wear cylindrical cardboard coverings over their entire heads featuring painted images and Lulu herself, as the personification of lustful, carnal desire, may append to herself cut-outs of her sex, becoming a cartoon-like nude.

Projection Designer Catherine Meyburgh, Set Designer Sabine Theunissen, and Costume Designer Greta Goiris all fulfilled the extraordinary task of creating visual magic and Maestro Lothar Koenigs along with the magnificent cast of Lulu were all instrumental in creating a memorable experience that will live on in our imaginations long after the final curtain.

by Lidia Paulinska | Dec 4, 2015

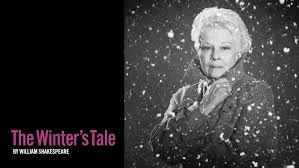

As part of their excellent “event cinema” series of filmed theatrical presentations, Fathom Events (fathomevents.com) screened William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale for a one-night-only showing November 30th at hundreds of movie theatres throughout the world. This masterful production was performed by the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company at the Garrick Theatre in London with Mr Branagh doing double duty as director and lead character Leontes and brilliantly complimented by a stellar performance by the incomparable Judi Dench as the redoubtable Paulina.

William Shakespeare penned thirty-seven masterful plays and 154 sonnets. Over the ensuing centuries there have been many attempts to categorize his plays, to fit them into a specific genre niche like “tragedy,” “history” and “comedy,” with many easily conforming to one or another of these categories, such as Hamlet, Macbeth, et al. who have earned their rank as true tragedies as evidenced by the body-strewn stages in their final scenes. Furthermore, those works that may be easily labeled “histories” include of course Henry IV, V, VI, Richard II & III, et al. since their primary focus is in fact on English history, albeit fictionalized like our contemporary historical novels.

Perhaps more problematic however, are those works that critics have attempted to label “comedies.” These so-called “comedies” share little in common with our 21st century American notion of what is in fact a true comedy. What often gives these classic works new vitality and relevance for a contemporary audience are well-positioned and thematically relevant directorial interpolations such as original music, zany by-play among the characters, imaginative staging and set design, etc.

Called “a timeless tragicomedy of obsession and redemption,” The Winter’s Tale is all of that and more. Wisely avoiding getting into the “genre controversy,” the scholar/critic Harold Bloom has observed, it is a vast pastoral lyric, “a mythic celebration of resurrection and renewal,” and of course a psychological novel of the first order, dealing as it does with the destructive force of the jealous rage experienced by Leontes toward his boyhood friend Polixenes whom he mistakenly believes to be responsible for the pregnancy of his beautiful and virtuous wife Hermione. It is Othello revisited, yet with refinement, for Iago has been internalized into the psyche of Leontes whose diseased intellectual activity renders him indifferent to moral good or evil.

If Act One deals with the destructive force of sexual jealousy personified by Leontes which causes the spiritual and physical death of his innocent wife Hermione, Act Two takes place sixteen years hence and, in contrast to the tragic events of the first act, opens on a high-flying festive note, featuring rollicking folk song and dance, foreshadowing Leontes’ mythical and redemptive reunion with a miraculous resurrected Hermione.

The final scene offers us a redemptively charged tableau vivant of Leontes, Hermione, and their sixteen year-old daughter reunited and thus a Leontes redeemed.

What distinguishes Shakespeare’s comedies from his tragedies is principally in the final scenes: In the tragedies, most of the principal characters wind up dead, whereas in the comedies, reunification and redemption prevail, marriages abound, and presumably everyone lives happily ever after, or as Shakespeare indicates elsewhere, “All’s well that ends well.”

And so too with Mr Branagh’s rich and compelling production: all was very well done indeed.

by Lidia Paulinska | Nov 28, 2015

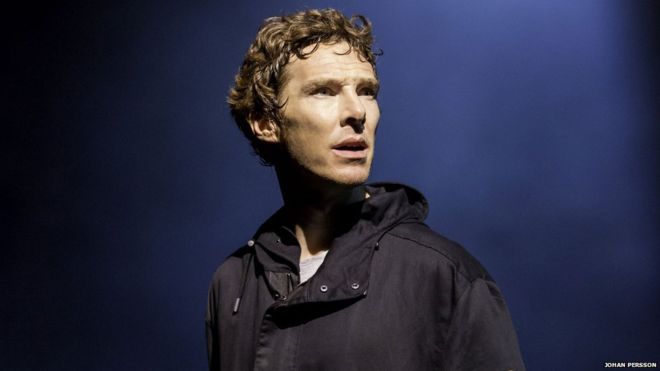

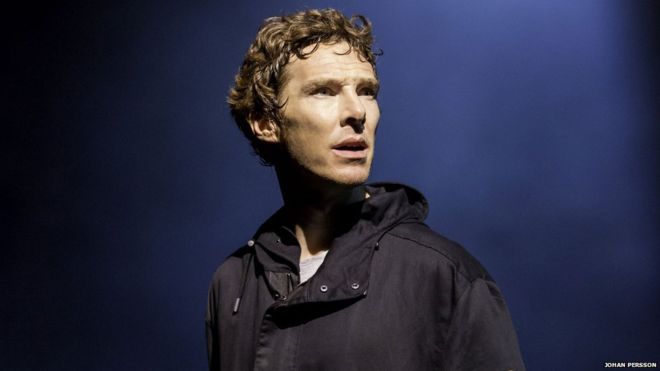

On the evening of November 10, 2015, thousands of fortunate theatre-goers world-wide were treated to a rare theatrical experience. They were offered the opportunity, through the good graces of Fathom Events, to witness a filmed live presentation of William Shakespeare’s immortal tragedy, Hamlet staring Benedict Cumberbatch of “The Imitation Game” fame in the title role. And a rare treat it was.

At the ripe old age of 400, Shakespeare’s iconic work, bursting at the seams with 4,000 vibrant lines of verse and prose, is as vital and relevant today as it was to audiences in the 17th century. An un-cut version of the play can run up to a daunting four hours, yet in an age of instant global communication and fast food, it nonetheless remains for us one of the greatest works of dramatic literature ever penned. Shakespeare not only belongs to the ages…he belongs to the world. In fact, his 37 plays have been translated into more than 100 languages and in the past ten years alone there have been seven professional productions in Arabic and over the years countless amateur and professional performances have been done in Yiddish.

Shakespeare’s plays were performed at the fortuitously named Globe theatre in Elizabethan London, a large round “wooden O” which was open to sky and could accommodate 1,500 spectators, with the gentry seated above and commoners standing below in the yard and having put 1 penny in a box at the entrance (origin of term “box office”) for the privilege. The bare stage thrust out into the yard where those Groundlings (also called “Stinkards”) stood and was completely devoid of any scenery. Consequently, the actor relied almost exclusively on Shakespeare’s dialogue to fix the location of the action. Such lines as “Here we are in the Forest of Arden” fulfilled this demand admirably. Costumes and props were minimal, limited to perhaps an occasional crown or sword, with Claudius no doubt wearing an identifying crown and Hamlet with sword in hand, dispatching the hapless Polonius behind the areas in Gertrude’s bed chamber. “Thou wretched, rash, intruding fool, I took thee for thy better.”

But that was then, and even though the language of the plays has remained constant throughout the centuries, what has changed radically has been the style of acting and the entire miss en scene, i.e., the sets and scenic design elements, the sophisticated computerized lighting, the elaborate costumes, etc., all determined by the culture of the time and place where the plays were performed. A minority of productions have remained faithful to the bare stage tradition of the Elizabethan period such as Richard Burton’s dynamic, bare-bones1964 Broadway presentation, performed on a bare stage with actors performing in rehearsal clothes (Burton hated period costumes). In contrast to that production, we need look no further than the over-the-top, sumptuously extravagant 1996 Kenneth Branagh film version which he directed and played the title role. His is a Hamlet that pulled out all the stops and was roundly criticized for it, not being “faithful” to the original text it was claimed. In one scene for example, Ophelia is in a padded cell sporting a straight jacket with little evidence in Shakespeare’s text of such a fate.

The National Theatre’s offering at the Barbican clearly leaned more to the Branagh rather than the Burton tradition, but with infinitely greater moderation, being quite legitimately, a richly staged production which captured the dark essence of the play. Here we have an Elsinore that is dank, cold and cavernous, dwarfing its doomed inhabitants, and being at once both elegant and decadent, fostering a thematic tone of foreboding that took on the qualities of a forbidding damp tomb, perfectly complementing the emerging tragedy that is unfolding.

And Shakespeare’s language? Mr Cumberbatch, ably backed by a splendid supporting cast, delivered his lines with an honesty and clarity that immediately engaged his audience and allowed Hamlet to come alive for us through the immediacy of the emotion he so effectively conveying. His was not so much the traditional “melancholic Dane” as he was a man beset by overwhelming passions and unbridled fury, the inevitable escape from which could only be realized in death.

If, as Hamlet extols to the visiting players, “the play’s the thing…”, then this well balanced, forceful production of Hamlet, splendidly sculptured for a 21st century audience, fulfilled that admonishment.

Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

by Lidia Paulinska | Nov 8, 2015

In 1983, a long time before Hollywood audiences fell in love with Computer Generating Imagery, also commonly known as “CGI”, the first experiment in a commercial motion picture film that combined live action and archival footage took place. This happened in Woody Allen’s groundbreaking film, “Zelig”, which he wrote, directed and starred in. Allen was the first filmmaker to use CGI in his production, which would be the beginnings of CGI, which would transform films into places we’ve never been before. CGI would forever assist the filmmaker in making his historical storytelling credible to all audiences.

“Zelig”, which is no doubt one of his most brilliant storytelling gems from Allen’s catalog of films is about a freak documentary about Leonard Zelig, who has paranormal abilities, like a chameleon who changes himself just by looking at someone; for example, in a presence full of Chinese people, he would change right before your eyes and become Chinese. The culmination scene is when Leonard one day disappears all of the sudden under unclear circumstances, and the psychologist, played by Mia Farrow, who is in love with him, and has been desperately searching for him until she saw him in the movie theatre movie screen, that was screening news from the world. At that moment, Leonard is standing amongst the crowd of people saluting the Adolf Hitler in Nazis Germany. Here is a beginning of a new computer technique that allowed Leonard to be pasted in the archive footage of that time.

The next major motion picture production using CGI was “Forrest Gump, directed by Robert Zemeckis, a story about a not very intelligent man that by accident became involved in historical events. The film won six Academy Awards, and many scenes would be never forgotten, as well as memorable quotes: “Life is like a box of chocolates…you never know what you’re gonna get.”. Forrest Gump was full of historical figures like JFK, Nixon or Elvis Presley. After the critical and commercial artistic success of “Forrest Gump”, CGI became the King of Hollywood.

“Zelig” was a black and white movie because the computer technology did not advanced to the point to solve matching colors. Ten years after “Zelig” was made, Forrest Gump made that possible.

However, computer technology is not that simple that can be seen from outside. It takes time and effort to build it. The producers of the last American hit, “Avengers”, were sharing their challenges, especially with the battle scene on the street of the city. The main characters were created in the computer and then carefully applied to match against the panoramic view of New York where the film was shot. Matching the colors became the ultimate challenge to the point that was easier to build the city on the computer. The production took one year.

Nothing easier is with animation movies that seem to be under full control of graphic computer designers. Building the reality using the CGI has the limitations as movement, gestures and mimic of the human face. But there are no doubts that technology is more and more advanced.

However, manipulation with computer images would not replace what is cinema about – the story.

The new HBO production “Hemingway and Gellhorn”, which was first aired on HBO on May 2012, utilized the archive footage from the domestic war in Spain, the Japanese invasion in China, and finally the Hemingways’ home in Cuba. Directed by Philip Kaufman, film is a saga about Hemingway and his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, starring Cliff Owen and Nicole Kidman.

According to the movie it was Hemingway, who made Gellhorn a full pledge war correspondent (describe what you see your own eyes, Gellhorn) and had a big influence on her writing. In exchange she was credited for inspiring him to write a novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls”. Serving as a reporter in Spain in 1936 was just beginning of her carrier which she became dedicated to the rest of her life. She went to Spain, China, Finland, Hong Kong, Burma, Singapore and Britain. She became more obsessed with it that Hemingway who, while she was away, stayed in their house nearby Havana, Cuba and was sending angry letters to her “Are you a war correspondent or my wife?”.

Now nearly everything that Hollywood produces is mainly CGI, most of them sacrificing the stories. However, CGI, can truly enhance films. They are essential tools that need brilliant filmmakers who have a real historical story to tell, like Woody Allen, Robert Zemeckis, or Philip Kaufman.

by Lidia Paulinska | Nov 7, 2015

As part of a valuable cultural service, Fathom Events presented Oscar Wilde’s classic comedy of manners,The Importance of Being Earnest at selected theaters in the U.S. for a one-night-only screening November 3, 2015. The performance was a filmed live production on October 8th, 2015 at London’s Vaudeville Theatre in commemoration of the play’s 120th anniversary.

As an iconic “comedy of manners” and one of the funniest plays in the English language, “Earnest” exaggerates the absurd superficiality of upper-class Victorian society, emphasizing the “importance of being earnest,” with “earnestness” having the connotation of intense conviction, dependability, and unflappable honesty. Being earnest was an integral part of the moral code of honor nominally practiced by upper-class Victorians. However, in practice, Wilde reminds us, “In matters of grave importance, style, not sincerity is the vital thing.”

The primary comic conceit in Wilde’s play deals with his clever use of the word earnest used both as an adjective in the afore mentioned sense, and Ernest as a noun…capitalized, minus the “a”, and being a proper man’s name. The confusion and interchangeability of the names between the two main characters, Algernon and Jack, the latter professing to be “…Ernest in town and Jack in the country,” forms the core of the play’s driving force of satire and duplicity, and an irony based on the characters’ violation of the very essence of being earnest through their abiding dishonesty. Jack is certainly not earnest when he pretends to be Earnest in the city but “Jack” in the country and the wit continues unabated throughout this Victorian romp.

Deftly directed by Adrian Noble (Amadeus, The King’s Speech) with a pitch-perfect cast featuring the incomparable David Suchet (Agatha Christie’s Poirot), as the irrepressible, irascible Lady Bracknell, The Importance of Being Earnests is rollicking high farce and wit at it’s very finest. Algernon is in love with Cecily, Jack is smitten by Gwendolyn, and both are forced to adopt the names “Ernest” because the objects of their affections cannot tolerate a man with any name other than “Ernest.”

Ironically of course, they forego the moral code of honesty associated with earnestness in order to satisfy their romantic interests. However, all is resolved in the end and the two couples are joined to live happily ever after.

In the final scene of the play, Lady Bracknell comments to Jack, “My nephew, you seem to display signs of triviality,” to which Jack replies as he and Gwendolyn happily exit stage left arm-in-arm, “On the contrary, Aunt Augusta, I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest.”

Curtain.

Review by Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

by Lidia Paulinska | Oct 23, 2015

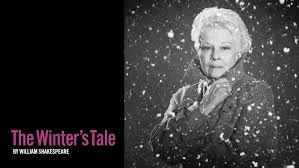

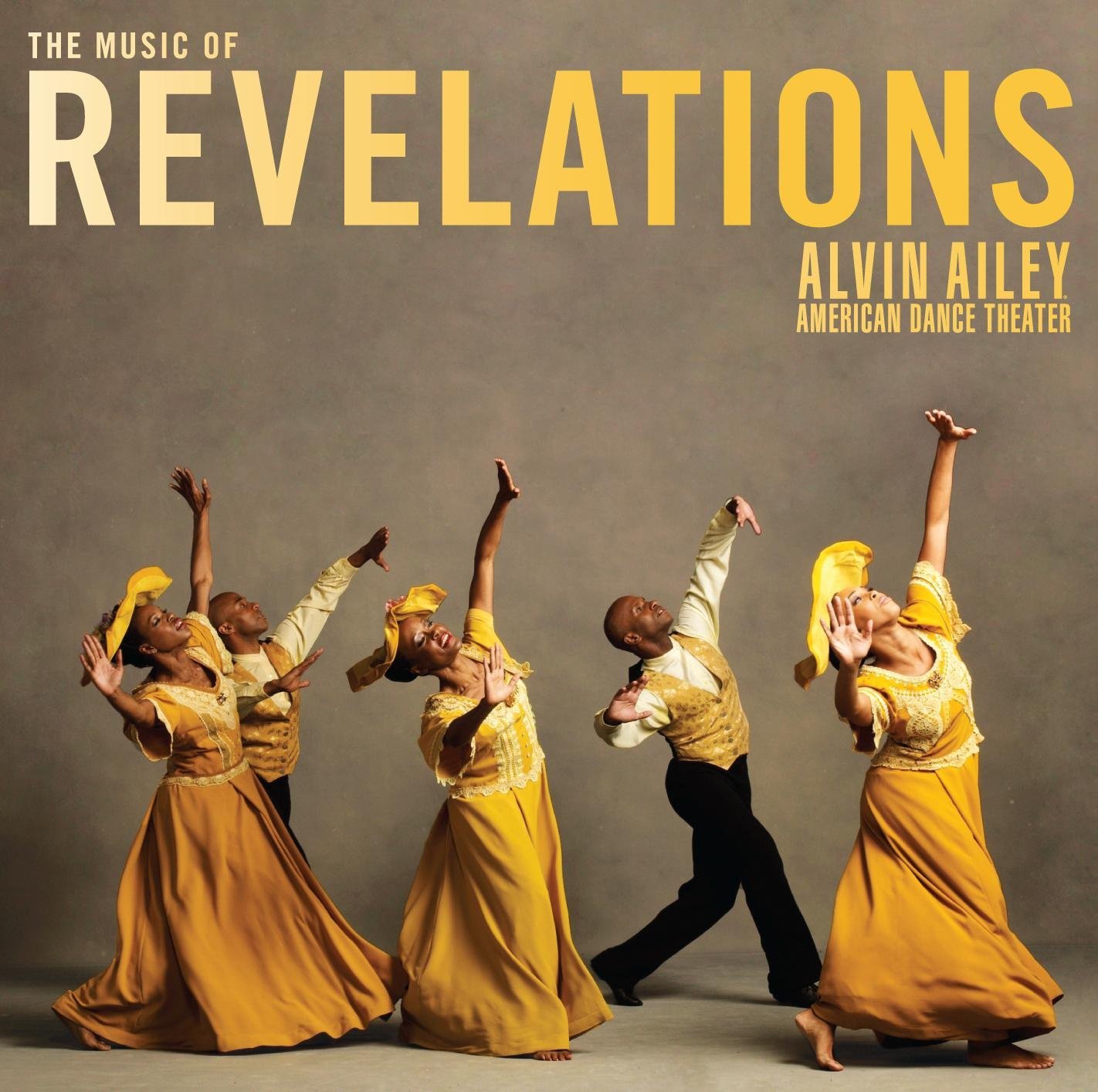

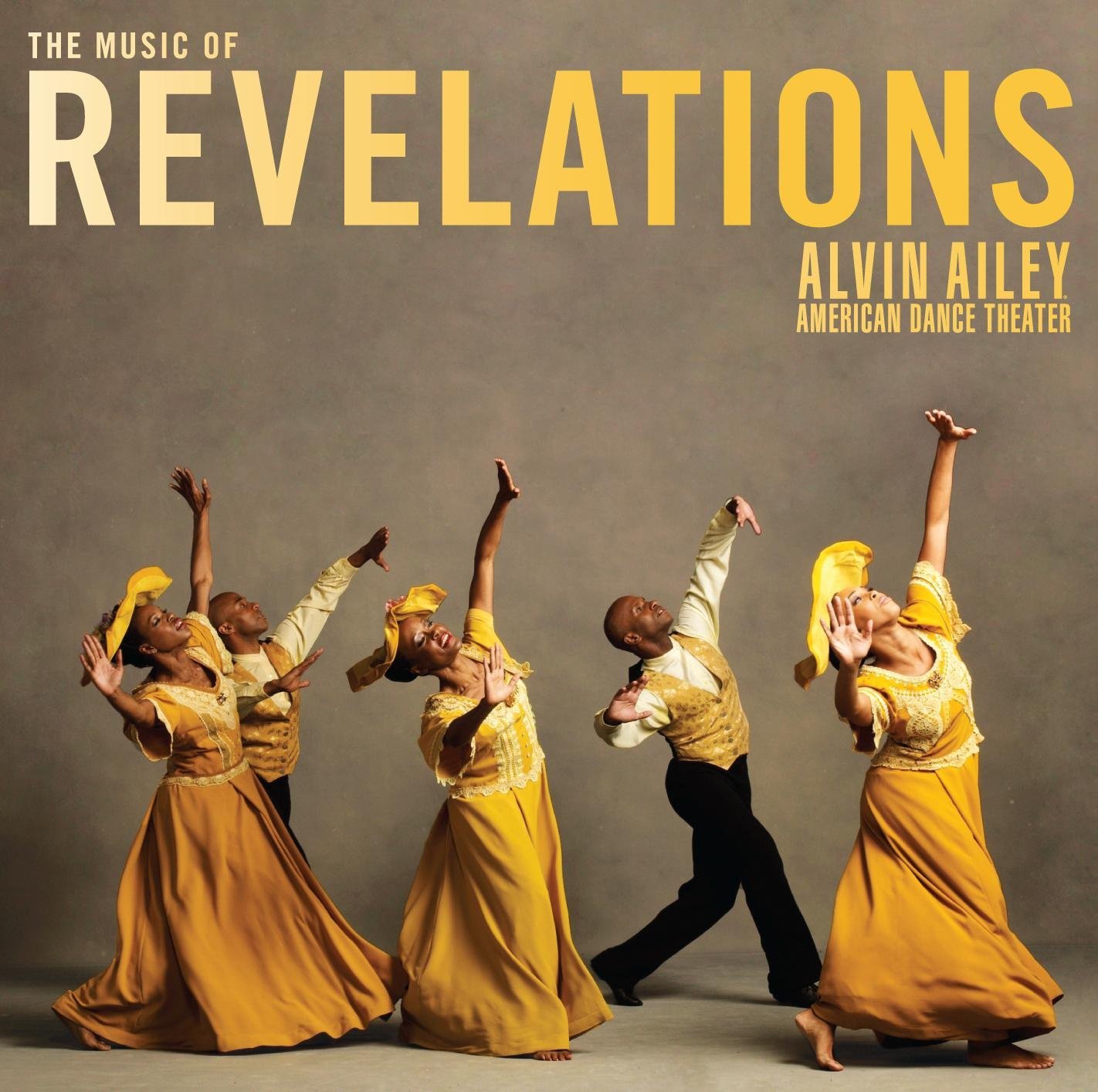

“Revelations,” Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre’s great masterpiece of modern American dance, was presented last evening along with three other spirited works for a one-night-only screening at selected cinema’s throughout the country, compliments of Fathom Events and Lincoln Center at the Movies: Great American Dance Series.

Alvin Ailey (1931-1989) founded AAADT in 1958 in New York City and it rightfully enjoys the distinction of being the first predominantly African-American modern dance company in the world. Ailey once remarked that he believed America’s richest treasures are to be found in our African-American cultural heritage … “sometimes sorrowful, sometimes jubilant, but always hopeful,” and indeed nowhere else in the vast panoply of the American dance tradition is that assessment more profoundly expressed than in his magnificent “Revelations,” Ailey’s 1960 paean to the rich spiritual tradition of the African-American experience in the gospel South.

“Revelations” is at once ritualistically soulful and rhythmically complex, incorporating as it’s musical motive force an array of deeply moving and spirited African-American gospel music and holy sermon blues reflecting the Black experience in America.

Ailey once described “Revelations” as a visceral recollection of a childhood in rural Texas during the Great Depression. It is a dance of deep human compassion, moving by turns from mournful oppression and sin (“Baked and I Been Beaten”) to redemption (“Fix Me Jesus”) and finally to ecstatic jubilation (“I Wanna Be Ready”), fostering a sense of reverent and rapturous community and inviting the audience to join in the redemptive celebration at evening’s end. And it is perhaps this vital sense of community, the immediacy of the connection Ailey creates between performer and audience,that has contributed to the enduring success of this masterpiece for fifty-five years … and running.

Complimenting this thematic content, one will find in the very make-up of the ensemble a communal structure. For example, what will not be found in Ailey’s troupe of highly trained performers is a prima ballerina or her male counterpart, a premier danseur, “star” principal dancers like those found in classical ballet companies such as the New York City Ballet or the Bolshoi, whose traditions and techniques date back to the 17th Century royal courts of Europe.

Another distinguishing feature of AAADT and modern dance in general which dramatically sets it apart from the classical tradition is not only a more “democratic” sense of ensemble, but also it’s musical sources (by contrast, the ballet typically utilizes works by such composers as Bach,Tchaikovsky, and others). Most obviously however is Ailey’s basic movement techniques and patterns, emphasizing linear line, horizontal “grounded” movement, and intertwining body images as opposed to the two dominant values found in classical ballet: jumps and leaps or so-called ballon, creating the illusion of the dancers momentarily floating in the air, and the tradition of performing with “turned out” hips and legs with the full weight of the body concentrated on the tips of fully extended feet, creating an unmistakable vertical line.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre’s iconic “Revelations” has been best described by The New York Times as being one of the great works of the human spirit.” It stands resolutely for what is good about America and humanity in general, and for this reason alone it’s immortality is assured.

Review by Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

Page 9 of 10« First«...678910»