by Lidia Paulinska | Sep 13, 2016

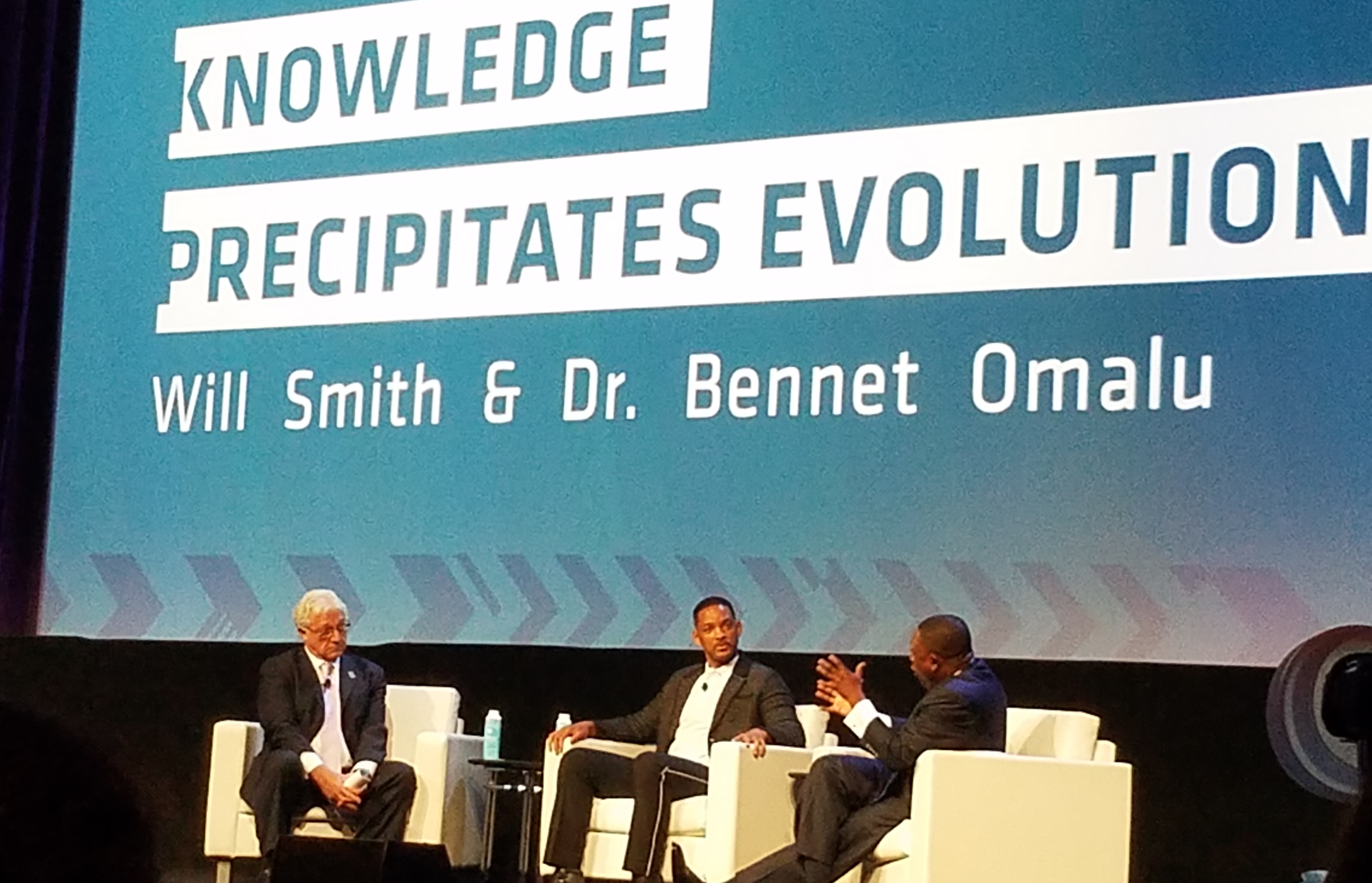

Biotechnology, September 2016 – The opening keynote for Biotechnology conference in San Francisco this past June was a brilliant pairing of two speakers – Forensic pathologist Dr Bennet Omalu and famous actor Will Smith.

What brought them together? The answer is – cinema.

Both of them are the characters of the movie “Concussion” that was released at the end of 2015 and many claimed that it deserved an Oscar nomination. It is the story of Dr Bennet Omalu (portrayed by Will Smith in the movie) who discovered and described a disease called CTE – Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy after a few dramatic accidents resulted in the early deaths of football players in Pittsburgh. For those who haven’t seen the movie I save writing a review, because it is worth going to see.

Dr Bennet Omalu talked on the stage about science for the sake of knowledge and the interrelationship of pure science and its faith. Will Smith talked about his reaction to the film. How he suddenly got concern about his son that likes to play football. Both men are very colorful characters. Omalu’s sense of humor and unstoppable laugh was dominating on the stage. Will Smith was talking about challenges in that role including Omalu’s accent and the laugh.

The film opened the public eyes at the challenges that players facing and shake the NFL world. Omalu who is dedicated to the science as investigating how the world works, and to this end, used his own money to investigate why the admired Steeler team football player Mike Webster, ended up his life alone, homeless and in unbearable pain. Omalu kept asking why that happened and why at so early an age. The road to acceptance of the discovery wasn’t easy but Omala believed and searched for truth no matter what.

As many attendees came being attracted by Will Smith presence they were taken by surprise and found Dr Bennet Omalu very interesting and compiling person.

by Lidia Paulinska | May 22, 2016

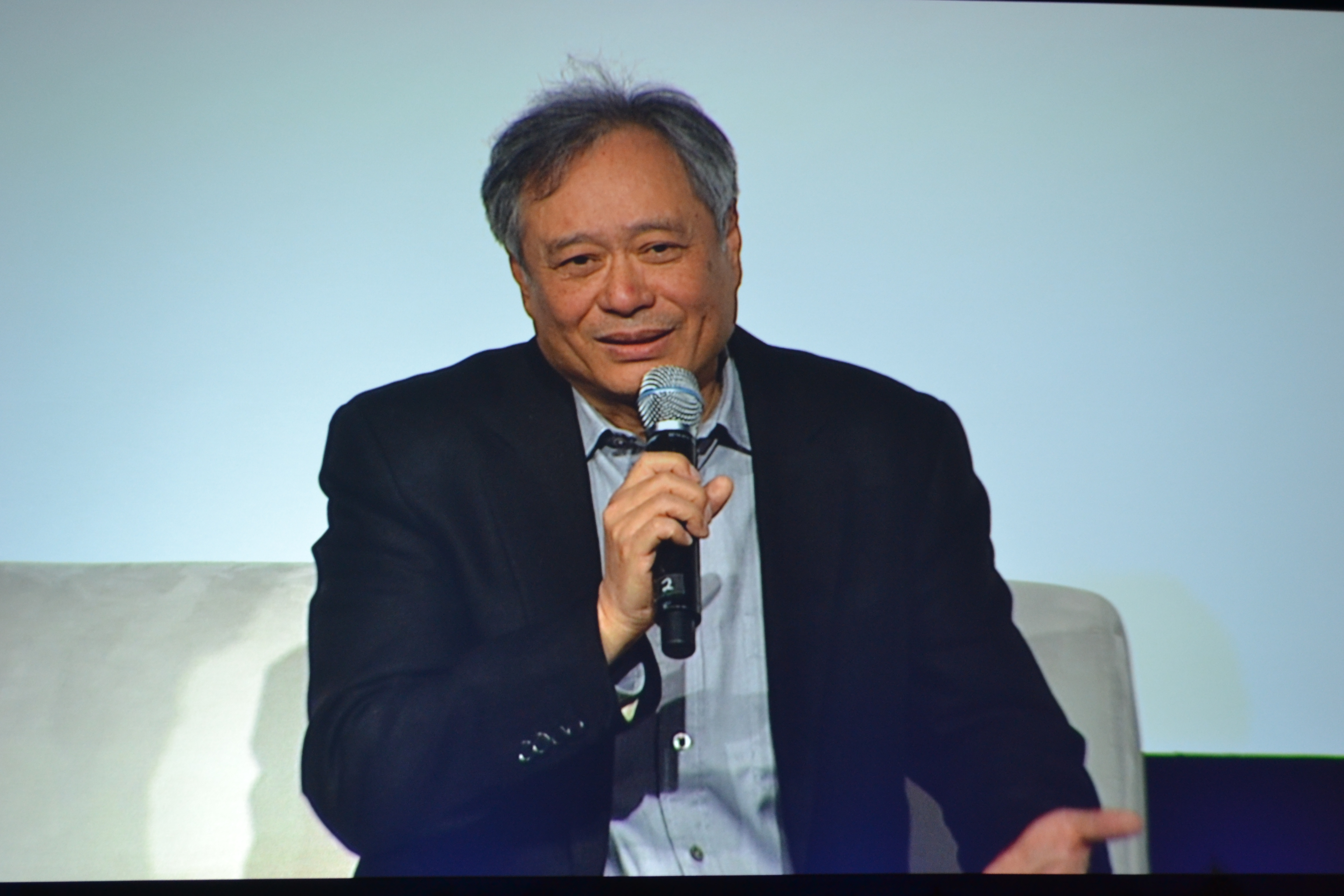

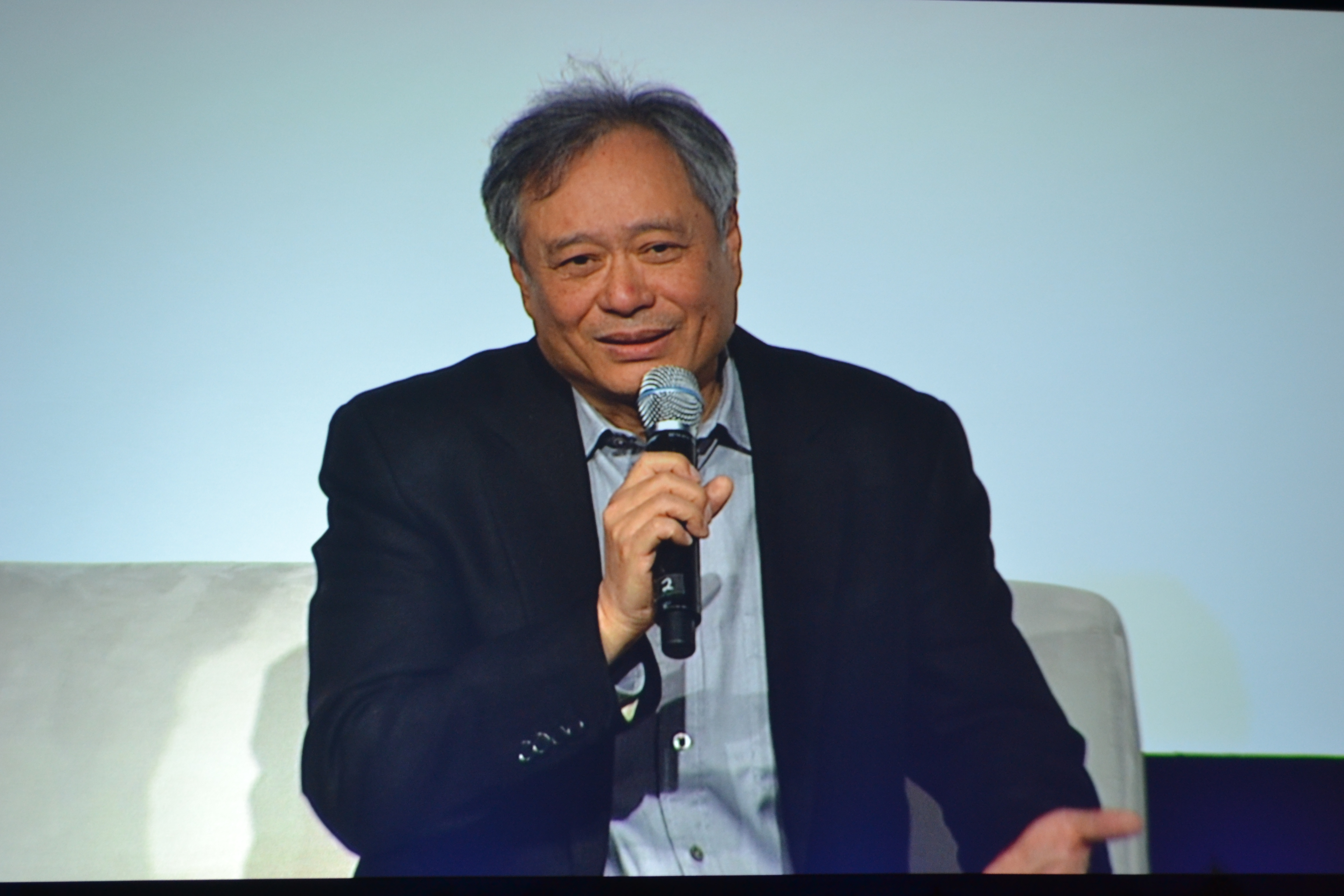

April 2016, NAB – At the start of NAB, SMPTE held the Digital Cinema Summit. The highlight speaker was Ang Lee who spoke following a discussion that HDR was not a tradeoff for future films, but was a technology that must be adopted due to its benefits in the story telling and immersive aspects of films. He spoke on pushing the limits of cinema.

One of the examples was with his film “Life of Pi”. In this film, the story is the enticing element. One aspect of the story was how to visually represent an irrational number and bring it to the screen as an experience. The film used 3D as an extra dimension in this story telling. HDR and HFR are also new technologies that can help with the story telling. HFR (High Frame Rate) has been under a recent resurgence as an alternative the traditional 24fps, and have been championed at NAB and other events by Doug Trumbull. Doug has been advocating 120fps content for both 2D and 3D films. Doug’s latest workflows include cameras, servers and editing flow for support of 3D, HDR, and 4K all at 120fps.

The workflow has over 40x the data of standard film, but produces an entirely different cinema experience. At NAB they had previews of an 11min clip of Ang Lee’s new film ‘Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,’ that was shot in 4K, HDR, 3D at 120fps. The preview was shown using dual Christie laser projectors and standard surround sound.

The clip provided an exposure to a new level of a “clarity of image” that has not been seen before by cinema audiences. This clarity of image defines a new challenge for the storyteller to be able to utilize this technology and enhance the story being told. The HFR feature also brings new cinematic capabilities to both 2D and 3D films. The HFR aspect also brings a new level of brightness and smoothness to the playback which can be used to enhance cinematic emotions and action without causing viewer fatigue. The overall common experience of the audience after viewing the clip – mostly related to technology and secondarily the cinematic use of the technology was “WOW!”.

by Lidia Paulinska | Apr 24, 2016

April, Fathom events – Arthur C. Clark, the renowned English physicist and science fiction novelist, once wrote: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” (Profiles of the Future, 1961), and this prescient observation is nowhere more apparent than today, 55 years later, with the phenomenal bursting forth of the Digital Age that has swept the globe over the past couple of decades and has impacted almost every aspect of our daily existence. Within this relatively brief period of time, digital technology has profoundly and irreversibly changed our lives … forever! We only have to ask ourselves, has our day-to-day routine been altered significantly by our smart phones, the internet, GPS, Hi-Definition TV & cinema , the inevitability of self-driving cars, or any of the other thousands of data tech innovations that pervade the very essence of our culture? I suspect most of us would unhesitatingly respond with a resounding “Yes, absolutely! “

You may justifiably ask, “What does all this have to do with Don Quixote?”, the venerable Russian ballet which was first performed in 1869 by the Ballet of the Imperial Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow? Well, the current production of the enduring “Don”, viewed live for one night only on April 10, 2016, has been seen by thousands of people in hundreds of theatres throughout the world on giant Hi Definition digital cinema screens (Pathe´ shot for the big screen with 5.1 sound and 10 HD cameras creating up-close and vivid pictures 3-times the definition of 1080p TV!) and is essentially based (with considerable variation) on the same work choreographed 147 years ago in Moscow by the great Marius Petipa (1818-1910).*

What does the Data Revolution have to do with a 147 year old Russian ballet? That question was answered for me the evening of April 10th in my local movie theatre.

Pass the popcorn!

Thanks to transformational digital technology which has forever changed our lives with smart phones, the internet, emails, Facebook, etc., more people viewed the Bolshoi’s Don Quixote the one evening of April 10th than had ever seen it in the past 147 years of it’s existence! And if that’s not revolutionary, I don’t know what is! In 1776 when the Bolshoi was founded, for example, it could take six weeks to send a letter by square rigger across the Atlantic from London to New York. Now we communicate with people on the other side of the planet or even circling the earth in space stations in milliseconds, one thousandth of a second, which is almost “indistinguishable from magic.”

Today’s Don Quixote by the Bolshoi resembles Cervantes’ novel in name only, with the character of the Don only occasionally making rather awkward non-dancing appearances on stage, with the “heavy lifting” of the evening left almost exclusively to the very able chorus which is indicative of Alexander Gorsky’s** reworking of the Petipa original. Both Petipa and Gorsky continue to be credited with the choreography in the program notes, and Leon Minkus’ original score continues to thrill, but the ballet has once again been “updated” to suite the changing expectations and tastes of a modern audience by Alexei Fadeyechev, (Bolshoi artistic director,1998 – 2000), yet still retains all the grandeur, perfection of style and precision execution the Bolshoi has been known for in its celebrated 240 year history.

In 1917, Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the famed Ballets Russes, who transformed the world of ballet, ushering it into the modern age, issued a challenge to Jean Cocteau who had asked him what were his ideas regarding a ballet they were producing. Diaghilev famously replied, Etonne-moi!! … “Astonish me!!” and the result was the immortal Parade, produced by impresario Diaghilev, designed by Pablo Picasso, composed by Erik Satie, and set to a story by Cocteau.

It has been said that our digital world can only become more incredible over time, joining art and technology, in ways now unimaginable. “Magic?” Perhaps … “Astonishing?” Unquestionably!

Etonne-moi!!

* Marius Petipa’s Don Quixote was subsequently modified over the years by rival Bolshoi choreographer Alexander Gorsky who completely transformed the ballet in 1900, creating a version radically different from Petipa’s original which infuriated him, and Gorsky’s version continues to be a permanent part of the Bolshoi repertoire to this day. Petipa, who was born in Marseilles, France, is universally considered to be the single most influential ballet master and choreographer in ballet history.

** Alexander Gorsky (1871-1924) was a renowned Russian choreographer and a contemporary of Petipas’, both serving at the same time at the Bolshoi. However it was never an easy relationship. A quick check with Wikipedia reveals, “The largest change that Gorsky made to Petipa’s (Don Quixote) choreography was the action of the corps de ballet. Instead of being a moving background as the corps often was, they became an important part of the drama.” (Wikipedia … 2016 Apr 8, 02:33 UTC….)

Rather than being nothing more than a moving part of the scenery, with Gorsky’s restaging, they bustle around the stage, “…breaking the symmetry and lines typical of Patina.” Gorsky added an element of playful lightheartedness to the new-found dynamism and significance of the chorus, characteristic the Bolshoi’s productions of “the Don” to this day. Alexander Gorsky is known today for his restating of Petipa’s ballets which include Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, and of course, Don Quixote.

by Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

by Lidia Paulinska | Feb 28, 2016

The Maltese Falcon is a 1941 film noir written and directed by John Huston which marked Huston’s directorial debut. His screenplay was based on the novel of the same name by Dashiell Hammet, the great American mystery writer known for his hard-boiled detective stories and the creation of one of cinema’s most enduring characters, Sam Spade, the detective in The Maltese Falcon played by Humphrey Bogart. Co-starring with Bogart was Peter Lorre and Sidney Greenstreet as Kasper Gutman, the “Fat Man,” who at 61 years old and 300+ pounds was making his film debut which won him a much-deserved Oscar nomination.

Interestingly, Bogart, Lorre and Greenstreet were to be reunited a year later in another Hal Wallis production: Casablanca. Ironically, Huston initially offered the role of Sam Spade to George Raft who turned it down because of the “inexperience” of the director.

And indeed as a director new to the craft, Huston made every effort to create an innovative, evocative and professional work on every level of production and he succeeded famously. For example, he planned every second of every shot to the most minute detail, shot-for-shot setups making sketches of every scene.* Much to Hal Wallis’ delight, the film came in on time and under budget and proved to be an instant success at the box office.

John Huston (1906 – 1987) of course went on to write the screenplays for the 37 films he directed, many of which are today considered classics. In addition to The Maltese Falcon he created The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), Key Largo (1948), The African Queen (1951) and many others.

One of the outstanding innovations of The Maltese Falcon was the brilliant cinematography of Arthur Edeson who was influenced by German Expressionism brought to America by German cinematographers during the 1920’s, a production style which is apparent in Edeson’s use of below eye-eye-level shots (for example, the low angle shots of Sidney Greenstreet when discussing the Maltese Falcon) and strong angular compositions combined with low lighting to create menacing shadows, all in black, white, and shades of gray.

Another innovation and by-product of Expressionistic technique shared with Orson Wells’ Citizen Kane which also premiered in 1941, was the low camera shots showing for the first time the ceilings of rooms in which the action was taking place, a commonplace today, but revolutionary for its time. Alfred Hitchcock, who in turn influenced Francois Truffaut, was to employ many of these Expressionistic techniques in his seminal films.

Huston’s film is the third version of the novel, the first having been attempted in 1931 with the same title and the second, titled Satan Met a Lady, starring Bette Davis was offered as a light comedy. By common consensus, Houston’s “Falcon” justifiably stands out as the true classic and a lasting cinematic treasure.

by Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

by Lidia Paulinska | Dec 4, 2015

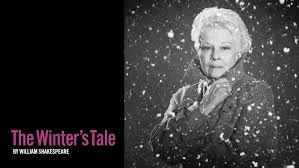

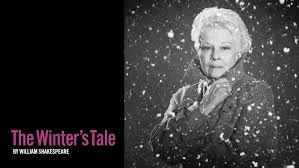

As part of their excellent “event cinema” series of filmed theatrical presentations, Fathom Events (fathomevents.com) screened William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale for a one-night-only showing November 30th at hundreds of movie theatres throughout the world. This masterful production was performed by the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company at the Garrick Theatre in London with Mr Branagh doing double duty as director and lead character Leontes and brilliantly complimented by a stellar performance by the incomparable Judi Dench as the redoubtable Paulina.

William Shakespeare penned thirty-seven masterful plays and 154 sonnets. Over the ensuing centuries there have been many attempts to categorize his plays, to fit them into a specific genre niche like “tragedy,” “history” and “comedy,” with many easily conforming to one or another of these categories, such as Hamlet, Macbeth, et al. who have earned their rank as true tragedies as evidenced by the body-strewn stages in their final scenes. Furthermore, those works that may be easily labeled “histories” include of course Henry IV, V, VI, Richard II & III, et al. since their primary focus is in fact on English history, albeit fictionalized like our contemporary historical novels.

Perhaps more problematic however, are those works that critics have attempted to label “comedies.” These so-called “comedies” share little in common with our 21st century American notion of what is in fact a true comedy. What often gives these classic works new vitality and relevance for a contemporary audience are well-positioned and thematically relevant directorial interpolations such as original music, zany by-play among the characters, imaginative staging and set design, etc.

Called “a timeless tragicomedy of obsession and redemption,” The Winter’s Tale is all of that and more. Wisely avoiding getting into the “genre controversy,” the scholar/critic Harold Bloom has observed, it is a vast pastoral lyric, “a mythic celebration of resurrection and renewal,” and of course a psychological novel of the first order, dealing as it does with the destructive force of the jealous rage experienced by Leontes toward his boyhood friend Polixenes whom he mistakenly believes to be responsible for the pregnancy of his beautiful and virtuous wife Hermione. It is Othello revisited, yet with refinement, for Iago has been internalized into the psyche of Leontes whose diseased intellectual activity renders him indifferent to moral good or evil.

If Act One deals with the destructive force of sexual jealousy personified by Leontes which causes the spiritual and physical death of his innocent wife Hermione, Act Two takes place sixteen years hence and, in contrast to the tragic events of the first act, opens on a high-flying festive note, featuring rollicking folk song and dance, foreshadowing Leontes’ mythical and redemptive reunion with a miraculous resurrected Hermione.

The final scene offers us a redemptively charged tableau vivant of Leontes, Hermione, and their sixteen year-old daughter reunited and thus a Leontes redeemed.

What distinguishes Shakespeare’s comedies from his tragedies is principally in the final scenes: In the tragedies, most of the principal characters wind up dead, whereas in the comedies, reunification and redemption prevail, marriages abound, and presumably everyone lives happily ever after, or as Shakespeare indicates elsewhere, “All’s well that ends well.”

And so too with Mr Branagh’s rich and compelling production: all was very well done indeed.