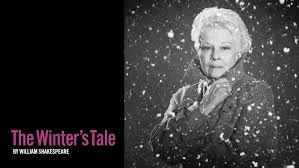

As part of their excellent “event cinema” series of filmed theatrical presentations, Fathom Events (fathomevents.com) screened William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale for a one-night-only showing November 30th at hundreds of movie theatres throughout the world. This masterful production was performed by the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company at the Garrick Theatre in London with Mr Branagh doing double duty as director and lead character Leontes and brilliantly complimented by a stellar performance by the incomparable Judi Dench as the redoubtable Paulina.

William Shakespeare penned thirty-seven masterful plays and 154 sonnets. Over the ensuing centuries there have been many attempts to categorize his plays, to fit them into a specific genre niche like “tragedy,” “history” and “comedy,” with many easily conforming to one or another of these categories, such as Hamlet, Macbeth, et al. who have earned their rank as true tragedies as evidenced by the body-strewn stages in their final scenes. Furthermore, those works that may be easily labeled “histories” include of course Henry IV, V, VI, Richard II & III, et al. since their primary focus is in fact on English history, albeit fictionalized like our contemporary historical novels.

Perhaps more problematic however, are those works that critics have attempted to label “comedies.” These so-called “comedies” share little in common with our 21st century American notion of what is in fact a true comedy. What often gives these classic works new vitality and relevance for a contemporary audience are well-positioned and thematically relevant directorial interpolations such as original music, zany by-play among the characters, imaginative staging and set design, etc.

Called “a timeless tragicomedy of obsession and redemption,” The Winter’s Tale is all of that and more. Wisely avoiding getting into the “genre controversy,” the scholar/critic Harold Bloom has observed, it is a vast pastoral lyric, “a mythic celebration of resurrection and renewal,” and of course a psychological novel of the first order, dealing as it does with the destructive force of the jealous rage experienced by Leontes toward his boyhood friend Polixenes whom he mistakenly believes to be responsible for the pregnancy of his beautiful and virtuous wife Hermione. It is Othello revisited, yet with refinement, for Iago has been internalized into the psyche of Leontes whose diseased intellectual activity renders him indifferent to moral good or evil.

If Act One deals with the destructive force of sexual jealousy personified by Leontes which causes the spiritual and physical death of his innocent wife Hermione, Act Two takes place sixteen years hence and, in contrast to the tragic events of the first act, opens on a high-flying festive note, featuring rollicking folk song and dance, foreshadowing Leontes’ mythical and redemptive reunion with a miraculous resurrected Hermione.

The final scene offers us a redemptively charged tableau vivant of Leontes, Hermione, and their sixteen year-old daughter reunited and thus a Leontes redeemed.

What distinguishes Shakespeare’s comedies from his tragedies is principally in the final scenes: In the tragedies, most of the principal characters wind up dead, whereas in the comedies, reunification and redemption prevail, marriages abound, and presumably everyone lives happily ever after, or as Shakespeare indicates elsewhere, “All’s well that ends well.”

And so too with Mr Branagh’s rich and compelling production: all was very well done indeed.