by Lidia Paulinska | Jan 18, 2016

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) the renowned French composer best known for his ground-breaking opera Carmen which premiered in Paris in1875 and is indisputably one of the most popular operas of all time.

Exactly three months after it’s opening night however, and on his sixth wedding anniversary, Bizet died of a heart attack at the age of 36 as a result of a chill he contracted after a swimming competition. Unfortunately, Carmen had not been well received initially since it was the first time a major opera realistically depicted everyday characters in leading roles rather than the traditional subject matter featuring the lives of royalty or mythological figures. Carmen herself, for example, is a cigarette-smoking, Gypsy factory worker of questionable virtue and this definitely did not set well with the opera-going public of the time.

Twelve years prior to Carmen in 1863, Bizet had composed another opera, Les Pecheurs de Perles (“The Pearl Fishers”), traditionally considered to be a minor effort and roundly criticized for it’s poor libretto and lack of any rousing arias while acknowledging adequate choric offerings. And although these shortcomings seem to hold true to this day, nonetheless, New York’s Metropolitan Opera succeeded in staging a captivating and often scenically stunning production viewed by thousands of opera lovers in neighborhood theaters throughout the U.S. thanks to Fathom Events and The Met: Live in HD series, currently celebrating it’s 10th Anniversary.

The scene is a pearl-diving village in the Far East, presumably Sri Lanka, and the plot deals with Leila, a Hindu virgin priestess and two men Zurga and Nadir who are vying for her affections. In this traditional love triangle, Nadir, played by tenor Matthew Polenzani, triumphs and he and Leila, depicted my mezzo soprano Diana Damrau, escape a fated death as baritone Mariusz Kwiecien as the vengeful Zurga, burns down the village in a rage of jealous spite.

All of the players perform credibly, perfectly vocalizing Bizet’s Romantically derivative yet rather engaging score, but the scene-stealer is the scenic values themselves. The set is appropriately functional and admirably serves the demands of the production, but the real spectacle is the stunning computer generated projections thanks to the magical wizardry of 59 Productions who are credited with production design. The opening scene for example is an underwater projection which takes up the entire proscenium of the Met stage and superimposed on the screen are two pearl fishers, actually ballet dancers supported by invisible cables a la Cirque de Soleil, who appear to be rhythmically swimming in a deep blue “ocean,’ complete with bubbles and rays of sunlight streaming through it’s depths. Sergei Diaghilev, the iconic Russian empresario who in 1909 founded the Ballets Ruses, was once asked by a set designer what he wanted by way of scenery, to which Diaghilev replied, “Astonish me!” and that’s exactly what the production design team succeeded in doing in this captivating production. We were astonished!

On balance, a valuable and entertaining theatrical experience and an opportunity to witness a pearl of an opera delicately extracted from an oyster shell of near oblivion in a lovely offering by The Met. Thank you and Bravo!

by Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

by Lidia Paulinska | Dec 10, 2015

The very words “Bolshoi Ballet” strike awe in the hearts of every devoted balletomane world-wide, and justifiably so. And on December 6, 2015, the world was indeed rewarded with an outstanding production of John Neumeier’s classic The Lady of the Camellias direct from Moscow compliments of Fathom Events, featuring the exquisite Svetlana Zakharova in the lead role of Marguerite, the consumptive courtesan who falls tragically in love with the young Armand, performed with style and strength by Edvin Revazov. This is a true ensemble production in which every element is essential to the outstanding success of the whole.

The story is a familiar one of star-crossed lovers based on Alexandre Dumas’ 19th century novel and operatically immortalized in La Traviata. Neumeier’s lyrical interpretation possesses a meditative, almost hypnotic quality as his dancers flow magnificently through Frédéric Chopin’s exquisitely romantic music, performed on pianos both on stage and in the orchestra pit and backed by the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra under the able direction of Pavel Sorokin.

This is a relatively brief, beautifully-paced ballet, running as it does in three, forty-five minute acts with two twenty-five minute intermissions. Because of this compactness, the audience is left in the end with a sense of peaceful contentment due in part to the work’s magically contemplative pace which mitigates to some degree the tragic nature of the storyline. The sheer beauty of the movement, the music, and the entire miss en scene imparts to us a serenity that defies analysis and lies beyond critical judgement; we select from the experience what we will, meditating on the aesthetics and making them our own. And that is the sign of a true classic.

by Lidia Paulinska | Dec 6, 2015

On December 2, 2015, in a live encore performance from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, Fathom Events presented Alban Berg’s masterful opera Lulu, featuring Marlis Petersen in the title role, Susan Graham as Countess Geschwitz and Johan Reuter as Dr. Schon. This was a very special performance, for it was to be Ms. Petersen’s final appearance in the role of Lulu after a professional career of delighting audiences here and abroad.

Alban Berg (1885-1935) was an Austrian composer, heavily influenced by Arnold Schoenberg and the culture of fin de siécle Vienna. He composed two seminal operas which were the most innovative and influential works of the 20th century: Woyzek (1925) and Lulu (1937). He is known for combining 19th century Romantic elements with Expressionistic idioms of the 20th century.

In this visually stunning production, the romantic lyricism of the music works in counterpoint to its atonality, and is complimented and contrasted with the stark, black and white expressionistic rear-screen projections, which, through their often violently changing patterns, create a kind of choral commentary on the action. Sudden giant swarths of black ink wash across the screen from one end of the huge Met stage to the other, and just as suddenly may dissolve into indiscriminate lines and circles with faces emerging from the seeming visual chaos. Characters on stage may wear cylindrical cardboard coverings over their entire heads featuring painted images and Lulu herself, as the personification of lustful, carnal desire, may append to herself cut-outs of her sex, becoming a cartoon-like nude.

Projection Designer Catherine Meyburgh, Set Designer Sabine Theunissen, and Costume Designer Greta Goiris all fulfilled the extraordinary task of creating visual magic and Maestro Lothar Koenigs along with the magnificent cast of Lulu were all instrumental in creating a memorable experience that will live on in our imaginations long after the final curtain.

by Lidia Paulinska | Dec 4, 2015

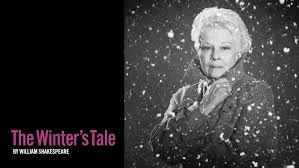

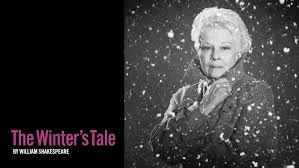

As part of their excellent “event cinema” series of filmed theatrical presentations, Fathom Events (fathomevents.com) screened William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale for a one-night-only showing November 30th at hundreds of movie theatres throughout the world. This masterful production was performed by the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company at the Garrick Theatre in London with Mr Branagh doing double duty as director and lead character Leontes and brilliantly complimented by a stellar performance by the incomparable Judi Dench as the redoubtable Paulina.

William Shakespeare penned thirty-seven masterful plays and 154 sonnets. Over the ensuing centuries there have been many attempts to categorize his plays, to fit them into a specific genre niche like “tragedy,” “history” and “comedy,” with many easily conforming to one or another of these categories, such as Hamlet, Macbeth, et al. who have earned their rank as true tragedies as evidenced by the body-strewn stages in their final scenes. Furthermore, those works that may be easily labeled “histories” include of course Henry IV, V, VI, Richard II & III, et al. since their primary focus is in fact on English history, albeit fictionalized like our contemporary historical novels.

Perhaps more problematic however, are those works that critics have attempted to label “comedies.” These so-called “comedies” share little in common with our 21st century American notion of what is in fact a true comedy. What often gives these classic works new vitality and relevance for a contemporary audience are well-positioned and thematically relevant directorial interpolations such as original music, zany by-play among the characters, imaginative staging and set design, etc.

Called “a timeless tragicomedy of obsession and redemption,” The Winter’s Tale is all of that and more. Wisely avoiding getting into the “genre controversy,” the scholar/critic Harold Bloom has observed, it is a vast pastoral lyric, “a mythic celebration of resurrection and renewal,” and of course a psychological novel of the first order, dealing as it does with the destructive force of the jealous rage experienced by Leontes toward his boyhood friend Polixenes whom he mistakenly believes to be responsible for the pregnancy of his beautiful and virtuous wife Hermione. It is Othello revisited, yet with refinement, for Iago has been internalized into the psyche of Leontes whose diseased intellectual activity renders him indifferent to moral good or evil.

If Act One deals with the destructive force of sexual jealousy personified by Leontes which causes the spiritual and physical death of his innocent wife Hermione, Act Two takes place sixteen years hence and, in contrast to the tragic events of the first act, opens on a high-flying festive note, featuring rollicking folk song and dance, foreshadowing Leontes’ mythical and redemptive reunion with a miraculous resurrected Hermione.

The final scene offers us a redemptively charged tableau vivant of Leontes, Hermione, and their sixteen year-old daughter reunited and thus a Leontes redeemed.

What distinguishes Shakespeare’s comedies from his tragedies is principally in the final scenes: In the tragedies, most of the principal characters wind up dead, whereas in the comedies, reunification and redemption prevail, marriages abound, and presumably everyone lives happily ever after, or as Shakespeare indicates elsewhere, “All’s well that ends well.”

And so too with Mr Branagh’s rich and compelling production: all was very well done indeed.

by Lidia Paulinska | Nov 28, 2015

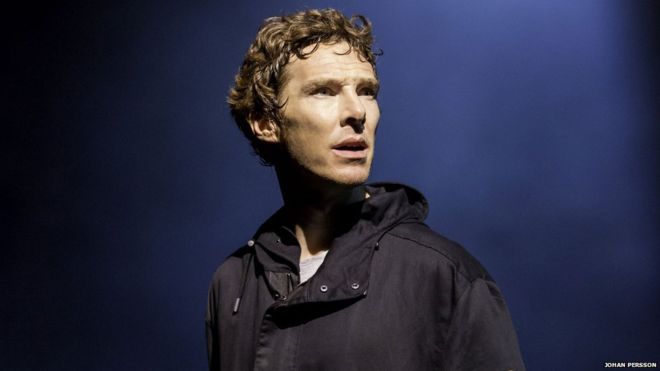

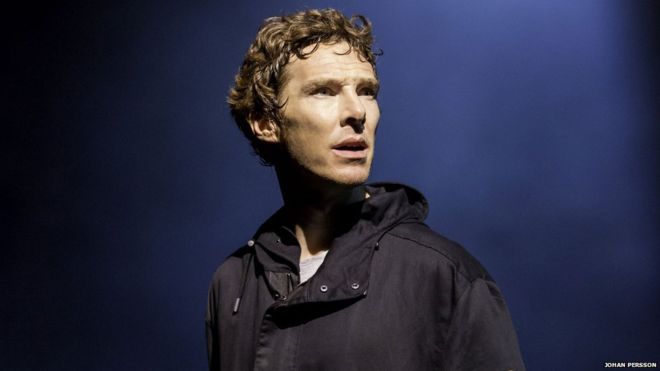

On the evening of November 10, 2015, thousands of fortunate theatre-goers world-wide were treated to a rare theatrical experience. They were offered the opportunity, through the good graces of Fathom Events, to witness a filmed live presentation of William Shakespeare’s immortal tragedy, Hamlet staring Benedict Cumberbatch of “The Imitation Game” fame in the title role. And a rare treat it was.

At the ripe old age of 400, Shakespeare’s iconic work, bursting at the seams with 4,000 vibrant lines of verse and prose, is as vital and relevant today as it was to audiences in the 17th century. An un-cut version of the play can run up to a daunting four hours, yet in an age of instant global communication and fast food, it nonetheless remains for us one of the greatest works of dramatic literature ever penned. Shakespeare not only belongs to the ages…he belongs to the world. In fact, his 37 plays have been translated into more than 100 languages and in the past ten years alone there have been seven professional productions in Arabic and over the years countless amateur and professional performances have been done in Yiddish.

Shakespeare’s plays were performed at the fortuitously named Globe theatre in Elizabethan London, a large round “wooden O” which was open to sky and could accommodate 1,500 spectators, with the gentry seated above and commoners standing below in the yard and having put 1 penny in a box at the entrance (origin of term “box office”) for the privilege. The bare stage thrust out into the yard where those Groundlings (also called “Stinkards”) stood and was completely devoid of any scenery. Consequently, the actor relied almost exclusively on Shakespeare’s dialogue to fix the location of the action. Such lines as “Here we are in the Forest of Arden” fulfilled this demand admirably. Costumes and props were minimal, limited to perhaps an occasional crown or sword, with Claudius no doubt wearing an identifying crown and Hamlet with sword in hand, dispatching the hapless Polonius behind the areas in Gertrude’s bed chamber. “Thou wretched, rash, intruding fool, I took thee for thy better.”

But that was then, and even though the language of the plays has remained constant throughout the centuries, what has changed radically has been the style of acting and the entire miss en scene, i.e., the sets and scenic design elements, the sophisticated computerized lighting, the elaborate costumes, etc., all determined by the culture of the time and place where the plays were performed. A minority of productions have remained faithful to the bare stage tradition of the Elizabethan period such as Richard Burton’s dynamic, bare-bones1964 Broadway presentation, performed on a bare stage with actors performing in rehearsal clothes (Burton hated period costumes). In contrast to that production, we need look no further than the over-the-top, sumptuously extravagant 1996 Kenneth Branagh film version which he directed and played the title role. His is a Hamlet that pulled out all the stops and was roundly criticized for it, not being “faithful” to the original text it was claimed. In one scene for example, Ophelia is in a padded cell sporting a straight jacket with little evidence in Shakespeare’s text of such a fate.

The National Theatre’s offering at the Barbican clearly leaned more to the Branagh rather than the Burton tradition, but with infinitely greater moderation, being quite legitimately, a richly staged production which captured the dark essence of the play. Here we have an Elsinore that is dank, cold and cavernous, dwarfing its doomed inhabitants, and being at once both elegant and decadent, fostering a thematic tone of foreboding that took on the qualities of a forbidding damp tomb, perfectly complementing the emerging tragedy that is unfolding.

And Shakespeare’s language? Mr Cumberbatch, ably backed by a splendid supporting cast, delivered his lines with an honesty and clarity that immediately engaged his audience and allowed Hamlet to come alive for us through the immediacy of the emotion he so effectively conveying. His was not so much the traditional “melancholic Dane” as he was a man beset by overwhelming passions and unbridled fury, the inevitable escape from which could only be realized in death.

If, as Hamlet extols to the visiting players, “the play’s the thing…”, then this well balanced, forceful production of Hamlet, splendidly sculptured for a 21st century audience, fulfilled that admonishment.

Lidia Paulinska and Hugh McMahon

Page 6 of 7« First«...34567»